Ed note: This is the latest post in the 'If I knew then what I know now' series, where leading members of the legal profession share their wisdom with the next generation of wannabes.

If I knew then that you didn’t have to be a lawyer to enjoy law, I would have relaxed more into my studies than I did, writes legal academic and Leverhulme research fellow Professor John Flood. By my second year I was regretting having started law. I originally had desires to do the right thing, make sure everyone had access to justice, but law school doesn’t teach you that...

![if-i-knew2]()

There were two events at law school that eventually changed my mind about law. The first was in Michael Zander’s English Legal System class. One Wednesday afternoon he asked us to go to a local police station and request the leaflets that were supposed to be handed to arrested people. Around 40 students hit the police stations of London, causing mayhem among them. Phone calls from the Home Office and Scotland Yard jammed the LSE switchboard. I loved it but some of my fellow students hated it.

The second was taking a class in anthropology of law. Law was taken out of the fusty courts into battles, food exchanges and Eskimo song contests. It opened my eyes. This stuff was real. I reinforced my choice not to be a lawyer by taking classes in Marxist theories of law, criminology, and legal theory, but not evidence or revenue.

But if I wasn’t going to be a lawyer, then what? My first thought was to put off deciding by taking an LLM. Warwick let me in to do research and I headed off to the Inns of Court to study barristers’ clerks. I became an anthropologist in Middle Temple, pitching my tent and observing this little known tribe. I followed them, I played football with them, and I drank with them. That last part led to some dark days, but I was happy.

I became a hybrid. One of my professors, William Twining, helped me go to the US to work at the American Bar Foundation (ABF). There was a wonderful mixture of social scientists and lawyers doing research on the legal profession, and they were being funded by the ABF. I combined this with doing a PhD in sociology with Howard Becker and Jack Heinz, which was a study of a corporate law firm. To do this I had to become a lawyer, as that was the only way to deal with lawyer-client privilege issues. Again, I pitched my tent and watched lawyers at work, how they talked with clients, how they billed their clients, and how they struggled for power inside the firm. It was a bit like having one’s own soap opera unfold before your eyes, only you have a role.

I think by this time I had realised I was an academic of sorts. But what sort? I wasn’t a "proper" legal academic; I was a sociologist but not many of them studied law and lawyers. I was clearly situated on the margins of whatever group I thought I belonged to. Although anxious I reconciled myself to this by understanding that if I played this the right way, I could more or less pursue my own ideas without much interference, and take charge of my life in a way that most people can’t do.

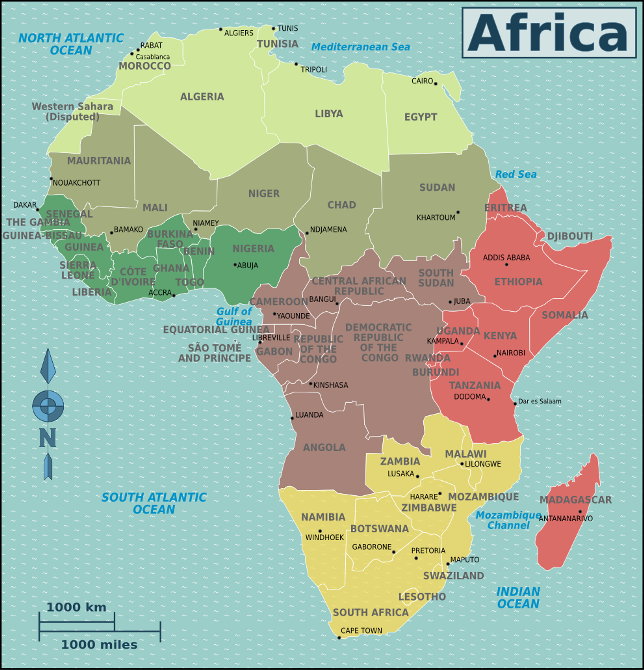

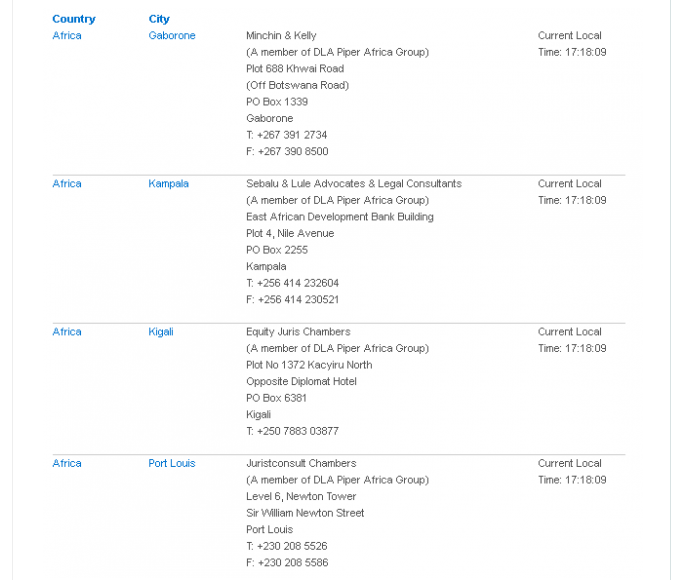

Finding myself at the University of Westminster close to legal London, I’ve continued researching the sociology of the legal profession. I’m omnivorous and study all lawyers, regardless of type. And I added globalisation to my interests on the basis that law didn’t appear to be globalising in the same way as finance, yet English and American lawyers were spreading their law firms and their legal institutions around the world. The key thing about my research is that it is empirical. When I want to know something about lawyers I ask them.

I have researched large law firms, lawyer-client relationships, ethics, the globalisation of insolvency, and I’ve been back to re-study barristers' clerks. They have changed a lot since my first time, but underneath I’m surprised by how much hasn’t changed. As an empirical researcher, I need funds to travel, to transcribe recordings and so on. I spend time applying for research grants, or I’m commissioned to do research. For example, both the Law Society and the Bar Council have asked me to do research for them. I have only one condition: I must be able to publish the results.

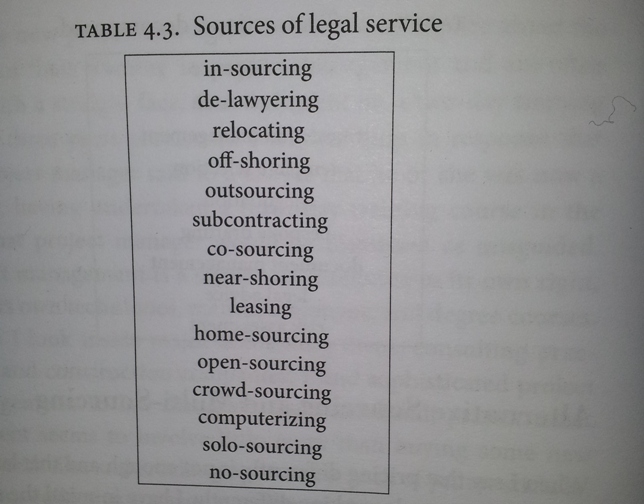

Now, I have a Leverhulme Research Fellowship for two years which is to study the new legal services market post-Legal Services Act 2007. This has brought me into contact with the Legal Services Board on whose Research Strategy Group I sit. I recently completed a project for them, with Morten Hviid of UEA, on the role of the cab rank rule.

Another of my teachers once said to me good research always upsets the status quo. Why not? It’s enjoyable and could achieve some good, which is where I started out.

John Flood is professor of law and sociology at the University of Westminster and Leverhulme research fellow. He blogs at John Flood’s Random Academic Thoughts (RATs).